Looking through the initial appearance of something in order to see the true underlying substance is a valuable ability. Whether you’re choosing whom to include and trust as your dearest friends, deciding to take on a business partner, or selecting a school for your child; looking past outward appearances to get closer to the truth can inform decision making. This is especially true in investing.

One way we get to know a business is through its accounts. Accounting isn’t as dry as it is socially acceptable to joke about. There are grey areas of accounting where some accountants are modern day mozart’s; they work on their sheet music like an inspired composition. Accounting is a representation of a business, in the same a way painting of Sydney Harbour is a representation of that harbour. There is always room for creative licence.

We’re focussing today on a corner of accounting concerning asset creation, in particular, something called “cost capitalisation asset creation”. The words are complex but the idea isn’t. We’ll focus on the word asset first. This is what most people think of when you say asset:

This is how the International Accounting Standards Board defines an asset:

An asset is a resource controlled by the entity as a result of past events and from which future economic benefits are expected to flow to the entity

You can see a house fits that definition nicely. You own the house because you bought it in the past, and you’ll get money out of it when you rent it or sell it in the future. The IASB definition of an asset is very general. It needs to be in order to facilitate the wide variety of businesses that accounting rules are applied to. Here’s a valid but less obvious example of an asset:

Carsales.com.au pays its team of 50 developers $200,000pa each. The development team develops a new smartphone app for people to browse and buy cars. The cost of developing the app, $10,000,000; is capitalised as an intangible asset called "software".

Compared to buying a house, this transaction isn’t as clear but is still a valid example of an asset. In this case though, they didn’t go out and buy the asset, they created it internally. Importantly, this $10m cash was paid to the development team like any other employee, but it wasn’t expensed like other wages.

If the company generated $100m in revenue and had no other expenses except the marketing team’s wages of $5m, then profit for this firm would have been (100-5) $95m. The profit would not have been stated as $85m, despite paying the development team $10m.

The $5m of marketing team wages were “expensed” and hit the firm’s profits. The $10m of wages for the development team were not, they were “capitalised” and a $10m asset was created. This is perfectly valid and you can see it fits the definition of an asset from IASB. This is “cost capitalisation asset creation”.

Analysts are generally uneasy around internally generated assets like this. Is the asset really worth $10m? What if conditions change and the app isn’t worth as much? What if their development team was overpaid and the app was never worth that much?

Honestly, you could be as philosophical and skeptical about any asset. Is your house really worth $1m? What if conditions change and it’s worth a lot less? What if you overpaid and it was never worth $1m in the first place?

We trust transactions like buying a house a little more than creating an asset because the transaction was done with the open market. Hopefully the market was pricing things correctly, even if it doesn’t always. We trust the market fractionally more than when accountants create an asset themselves. We’ll see why with a real example.

KC just finished looking at Spotless. It’s a respectable firm in a reasonable industry with some interesting accounting. When the government or a business wants an event catered, cleaned, or a whole host of other facility management tasks, they turn to Spotless or one of its competitors. Spotless was bought in August 2012 by a private equity firm (PEP) for $720m. PEP amputated some bad business divisions and 18 months later they sold it back to the Australian stock exchange (your super fund) for a cool $1.75 billion. Not a bad turn around.

Any investor has to look closely at the changes that firms like Spotless are subjected to under such short periods of time. PE firms serve a valuable purpose in modern capital markets. The buying out of entire firms to replace substandard management and reconstruct businesses after years of neglect is one such purpose. With the power of total ownership, PEP came in and injected a CEO with an excellent history and sold off poor quality business divisions that should have been let go a half decade earlier.

Investors have to be aware however, that private equity is in the business of quick turnarounds. There is an incentive to make decisions that will create a better looking business for sale tomorrow, at the expense of the long term.

One accounting decision I might put in this bucket was the decision to capitalise bid costs. Spotless gets its business by winning contracts to clean and cater. It has to bid for these contracts. Writing bids and creating slide decks costs employee time and these employees get paid a wage. In the lead up to the float, accounting was changed so that the salaries of these employees writing bids were capitalised instead of expensed. A little more creatively, these salaries were capitalised whether or not the bid had been won yet. Whilst many real changes had actually been done to business, this one was purely an accounting change and would immediately make this business appear more profitable than it used to be.

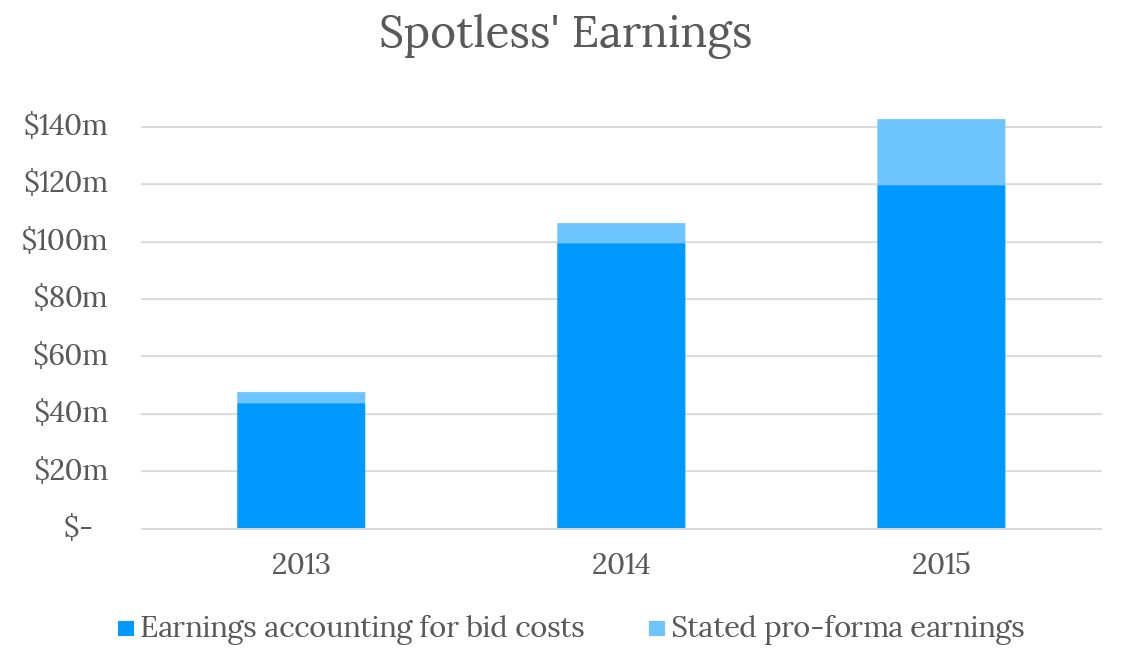

- In 2013, just prior to the float, $5.7m was capitalised and in doing so, expenses were hidden and profits boosted 9%.

- In 2014, immediately after the float and when shares were still held in escrow, $10.2m of bid costs were capitalised, boosting profit that year by 7%.

- In 2015, another $33m of net bid costs were capitalised, boosting profits by a handsome 19%.

By the end of 2015 there were $50m of “other non-current assets” on the books, an asset created by capitalising these bid costs instead of expensing them against profit. PEP and the accountants haven’t done anything wrong here. There’s nothing in the IASB rules that say they can’t do this. The auditors have signed off with clear conscience. But as an investor, you would be overestimating the earning power of the business if you took the statements at face value. This accounting treatment overstates the earnings power of the business today.

In the future, if this is left to run, the accounting decision will actually understate the performance of the business. If the firm continues to spend circa $20m per year writing bids and replying to tenders, this “true” cost will be far exceeded by the amortization on a large pile of these “other non-current assets” it is creating today.

Holding everything else constant, nothing in the underlying business of cleaning and catering would have changed, but it will appear to be getting less profitable. The accounting is effectively borrowing “profit” from the future so it can be shown in the statements today.

Only a couple months after the release of the 2015 accounts, the new CEO pared back some of the old accountant’s creative work. In addition, Spotless lost one of the large bids it had been working on and wrote off $7m of “other non-current assets”. The market then changed its opinion of the business. In six days it went from saying it was worth $2.4 billion, to $1.1 billion. The underlying business had likely not changed materially.

To return to our painting analogy. Sydney Harbour hasn’t changed a lot in six days, but the artist might decide to mix in a different set of colors to what they had been using before. Accounting is a representation of a business, and in this case, a little creative licence was taken. Being aware of creative accounting lets an investor see through the stated numbers and get closer to the true underlying business and its performance. I believe looking through the gloss and appraising the real substance of something is a valuable approach inside and outside of business.